I had originally intended to do my Yuma trip in the fall, when the weather turned cooler and far more skate-friendly than the typical summertime highs of 118 degrees would allow. Renee, however, had immediate plans to make a weekend trip to retrieve her father’s ashes, and asked me if I would like to come along for the ride. She was aware that I had a tour itinerary already well-planned and ready to go, and offered to be my skating sidekick for my intended misadventures. In addition, she offered to foot the bill for a swanky hotel crash pad for the weekend, if I would pick up the dinner-and-gas tab… an offer that I heartily accepted. Thus, I happily traded the hardships of camper living for plush amenities like a cold pool and a king-size bed for this brief leg of my overly ambitious summertime tour.

We were up and at ’em bright and early on Saturday morning for our long haul to bordertown. The itinerary could not have been more packed with diversions. We would be spending the bulk of our time driving straight through the heart of Arizona’s military-industrial complex, a huge swath of southwest desert that have been historically earmarked for training bases, and bombing and gunnery ranges. From the moment that we left the confines of Phoenix, we would be traveling back in time through the widespread and rampant abandonment of World War II and Cold War homefront battlefields.

Above: Gila Bend Welcome Sign and RF-101C Voodoos, Gila Bend, Arizona. Saturday, July 8th, 2017.

We were in Gila Bend at 7 am sharp. Roadside America had a few fun features on our itinerary. There was the offbeat humor of the “Welcome to Gila Bend” sign that boasted 1917 inhabitants, five old crabs, a metropolis of solar panels, and… curiously… a Volcom Stone advertisement. There were the staunch (but clearly aging) gate guardians at the Gila Bend Municipal Airport, a pair of RF-101C Voodoos that served the bulk of their overseas operational lives together, and were destined to spend their retirements forever married, standing side by side at the entrance of the local municipal airport. There was a massive chunk of the World Trade Center, installed at the main street city park as a 9/11 memorial. And there were several fabricated steel dinosaurs that had been crafted by a local artisan, and prominently peppered throughout the city at a bevy of gas stations and convenience stores. But the real prize of the morning was stuffing ourselves full of breakfast at The Space Age Restaurant, a stylistic and architectural throwback to the Mercury and Apollo missions and the moon-man hysteria of the 1960’s. The ham and swiss omelets here are out of this world. Pun totally intended.

Above: Space Age Restaurant exterior (left) and mural detail (right), Gila Bend, Arizona.

Above: steel T-Rex sculpture at Eddie’s Tire Shop (left) and 9/11 Memorial Park (right), Gila Bend, Arizona.

You can’t see Dateland Auxiliary Airfield from the interstate. From car-window level, the long-abandoned runways and tarmacs are shrouded in thick desert vegetation. Interstate 8 bisects the property; if you keep your eyes wide open and alert for a brief few-tenths of a mile, you might pick out the concrete foundations of the former barracks just beyond the shoulders. A little to the north, though, the runways still remain baking in the sun, left lying undisturbed since they were decommissioned in 1955. The problem is that, in order to see them at all, you have to be either “practically standing on top of them”; or, literally standing on top of them. I’ll give you intrepid guys and gals one guess to figure out which plan I was going with this weekend…

Above: “Or lost out there, far away on the road, those lights…”. Dateland AAF, Dateland, Arizona.

There are prominent signs at the peripheries of the property that warn of exceedingly grave consequences to trespassers. Death could be imposed as a punishment; these fellows clearly weren’t f’n around. Renee was a little bit nervous, naturally enough. But I wasn’t. I’m a skateboarder and an avid urban explorer; trespassing is old news to me.

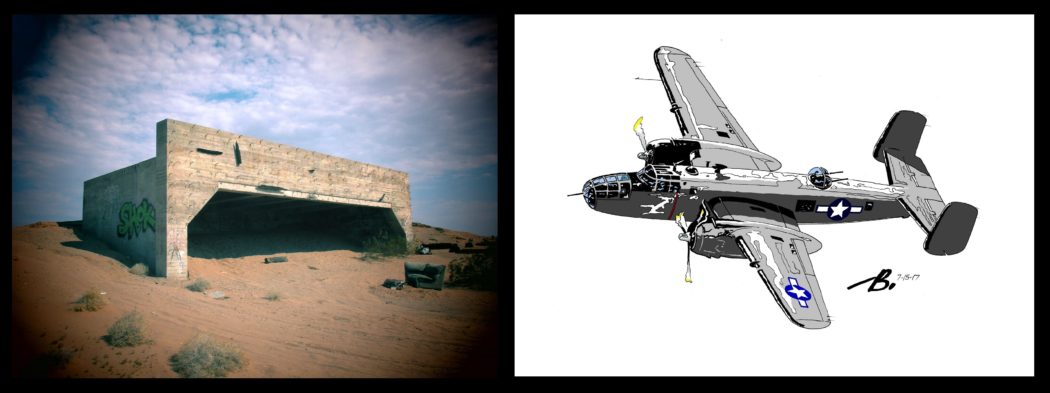

Above: Concrete bunker (left) and North American B-25J Mitchell (right), the bomber type that was stationed at Dateland AAF, illustration by the author.

Up ahead, just off to my right, I spotted a series of large, plastic orange spheres suspended on the power lines that paralleled the road; those were the telltale signs of a nearby runway that I was looking for. Undaunted and unperturbed, I steered the Prius straight onto the old bituminous runway… the “asphalt” has since been reduced to loose gravel aggregate from idly baking in the desert sun for well over seventy years… and proceeded to give her the grand tour of the property.

The place was astronomically huge. The runways approached nearly a mile long apiece, and the tarmac easily held five or six solid city blocks’ worth of real estate. Thanks to my exhaustive research and encyclopedic knowledge, I was able to point out where every hangar, workshop, mess hall, and latrine would have been in 1944. The only building left standing, however, was a sand-filled concrete bunker that had been used to sight and test-fire the fifty cals that were stuffed, sometimes eight to twelve at a time, into the noses of B-25 Mitchell bombers. On the south side of the property was a humongous (and apparently, quite prosperous) date farm, with rows of irrigated date palms standing tall and strong against the bright, blue morning sky. The five-dollar date shake that we bought at the exit-ramp gas station was almost sickly-sweet, the fruit fibers stubbornly clogging up our skinny straw all the way to Yuma.

Deterrents to adventure abound everywhere. The Bridge To Nowhere was only exceptional in the depth and breadth of its multitude of posted-paranoia warnings. First were the threats of criminal trespassing charges to all that might dare to encroach the peripheries of the property. I just left Dateland, buddy, where I could’ve died; I’m not particularly afraid of your pansy-pants little signs anymore. Next, there were sobering warnings of unsafe and deteriorating road conditions immediately ahead. Apparently, these blokes have never driven around on an abandoned airfield. Then, there were pointed engineering assessments regarding the inherent instability of the bridge itself. Bridges aren’t safe, big deal. Lastly, there were… the bees. Bees…? Are you f’n serious right now…? Well, the sign was certainly trying to look serious and impressive enough, I suppose. But after running the gauntlet of far more frightful dangers, I really couldn’t be all that bothered by the highly unlikely threat of some stinging insect invasion. It seemed like some sort of sick bureaucratic joke, or a governmental attempt at a merry prank. There wasn’t a single bee anywhere in eyesight or earshot, for Pete’s sakes. The spindly little guardrail that was left to stop us was no match at all for my tall legs, although Renee did need a bit of a helping hand to circumvent it.

Above: The Bridge to Nowhere; Tiny Church (Loren Pratt’s Little Chapel), US 95 north of Yuma, Arizona.

You’ve probably never seen a gun that can lob a small nuclear bomb a mile across a battlefield. I sure as hell haven’t. But this cannon can. They don’t really call them “small nuclear bombs”, of course; that would sound needlessly crass and inhumane. The notion of firing nuclear bombs in such close proximity to our own boys’ boots on the ground would seem foolhardy at the very best, and downright stupid at the very worst. These, right here, are not “small nuclear bomb tossers” at all; they are, in military-jargon-speak, “tactical nuclear weapons”. It’s a perfect example of what our government names stuff when they want to do something really unwise, but make it sound mindlessly bland in an effort to minimize our imaginations into thinking that they’re actually doing something quite noble in our better interests. These guns have been fired, of course, but never at any foreign army or enemy. The only places where these toxic shells have ever fallen is in the desert wastelands of America, also known as the Yuma Army Proving Grounds.

Above: our welcome to Castle Dome City (left), and a tactical nuclear bomb-lobber (right) on US 95 north of Yuma, Arizona.

Sure, the baking desert sun might be absolutely relentless. But there is still no hell quite like a crowd of loud, annoying, uncivilized foreign tourists. We had passed them in their rental SUV’s, moping along at a cautiously annoying twenty miles per hour, several miles back. If I could have run them off the road into some of that “unexploded ordinance” that the roadside signs continually warned us about, I certainly would have. Now they were right behind us, clogging up the narrow wooden pathways of the Castle Dome Mining Museum. Where are those tactical nuclear weapons when you really need them…?

Above: church at Castle Dome City (left), and a creepy manikin (right) waiting in wait, somewhere in the dark corners of Castle Dome City.

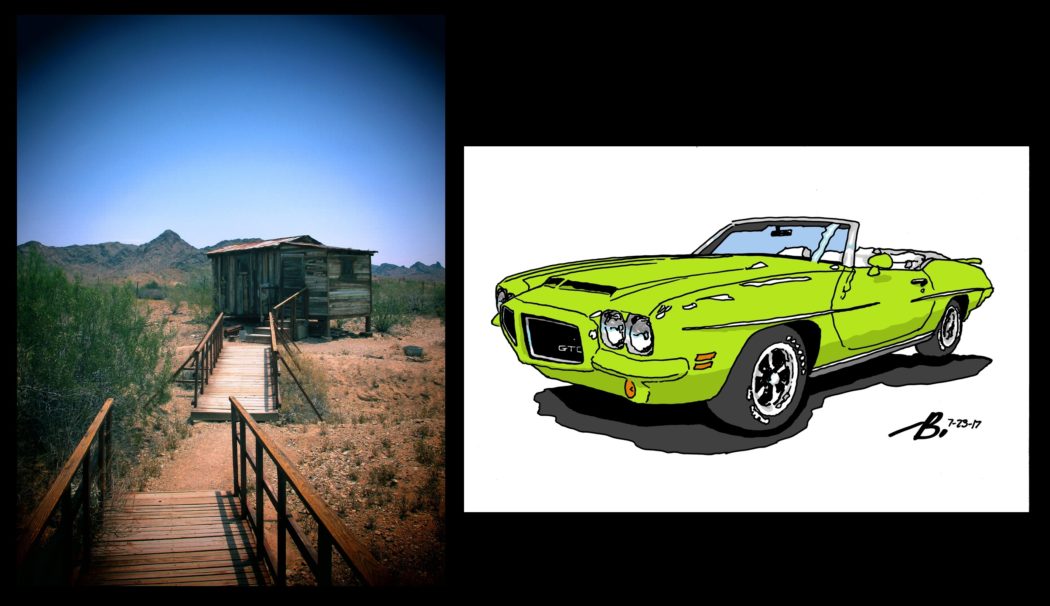

Renee and I were in a hurry. We were trying to stay one step ahead of the tourist crowd at all times. The temperature hovered in the 110’s, and the sun was high and bright in the desert mountain sky. A slight breeze stirred up dirt and dust that blew through the buildings of this long-abandoned mining ghost town. Besides the tourists and the sole gatekeeper/host/tour guide of the property, the town was completely uninhabited. The only “humanity” to be found on the premises were a series of creepy mannequins, dressed up in period-correct costumes. Every room you entered and every corner you turned, you ran the risk of running straight into one of these un-human characters. Or, a foreign tourist. Same difference, I guess. This place was consistently full of silent surprises. It was hard to imagine people living like this out on the far fringes of the desert. Tiny one-room shanties with small spring mattresses filled the nooks and crannies of this bustling commercial micropolis. There was no air conditioning, little ventilation, few signs of running water, and no showers; it must have been a personal perspiration and hygiene hell. Yet people persisted, and even prospered, out here on the high desert for over a hundred years, right into the mid-1970’s. The tour guide made sure that we didn’t miss the perfectly preserved 1971 Pontiac GTO clone-convertible and the Porsche 911 lovingly protected by the last of the shanty-sheds at the far peripheries of the property. Apparently, the last remaining residents of Castle Dome had remarkably refined tastes in sports and muscle cars.

Above: walkway to the sawblade shack (left), and that beautiful Pontiac GTO (right), Castle Dome City, illustration by the author.

Kennedy Skatepark was quite a surprise. I’ve never seen a skatepark quite like this in my entire life… and trust me, neither have you. It’s a huge, but sparse, outdoor facility that appears professionally built in some places, and nightmarishly amateurish in others. The bowl was hardly skateable; the Skatelite-surfaced mini-ramp, however, had been built solidly enough that it was still a heap-ton of fun, even in its rapidly deteriorating state. The most remarkable feature, though, was the mellowly graded downhill ditch that ran right through the middle of the park, and terminated at a wide-rimmed bowl at the bottom. This was carving nirvana, and a once-in-a-lifetime skating opportunity for Renee. Here was a place where she could learn all of the basics of carving and pumping in an immensely enjoyable way, and at a bare minimum of risk. It was far too hot to skate it mid-day, of course, so we decided to come back the following morning instead when the temperatures would be far more manageable. In the meantime, she had some immediate skateboard upgrading to do.

Above: Kennedy Skatepark, Yuma, Arizona.

The local brick-and-mortar skate shop, Bordertown, was just a few blocks away. We went in to get some harder bushings for her brand-new Santa Cruz cruiser complete; the stock bushings were a wee bit too soft and unstable for her tastes. The salesman was immensely friendly and helpful; she really liked him a lot. So much so that she impulse-bought a couple pairs of Vans lo-tops before she left. Most skate shops would never see much of a market in the middle-aged mom demographic. Even fewer would take the time (or the energy) to walk a gal like Renee through the finer points of durometers, barrel bushings, and cup washers. But thankfully, Bordertown is a little bit smarter and more positively enlightened then most skate shops Renee has experienced thus far. And they’re winning. That quick $6-to-$60 upsell was swift, silent, and deadly evidence of that.

San Luis Skatepark, San Luis, Arizona.

My next two stops, the San Luis and Somerton skateparks, were largely for the benefit of Jeff Greenwood at Concrete Disciples. Both are agricultural towns that reside deep in the heart of boundless cotton fields that extend far over the distant horizon in every imaginable direction, just north of the US-Mexico border; again, skateboarding exists in the most unlikely of places sometimes. I got lost far too many times trying to find the parks, which gave Renee a few mad fits and spontaneous chuckles. The parks weren’t great. They weren’t even particularly good, if I had to be totally honest about it. But searching them out and documenting them for Jeffo made for a fun afternoon of hijinks and high adventure.

Somerton Skatepark, Somerton, Arizona.

“Renee really picked a great one this time. This hotel is the bee’s knees. We drove, walked, hiked, and skated for about fourteen hours straight today through the hottest and sandiest hell that I could have ever imagined, and we’re both sweaty, filthy, and bone tired. But our room features ice-cold air conditioning, crisp white linens, and by far the biggest bed that I’ve ever laid my eyes or my ass upon. Just outside our window, there’s an olympic-sized amoeba pool ringed by tall palm trees and gas grills. The sounds of splashing water and the smells of burning beef are far too tempting to resist. We came, we saw, we cheered, we changed straight into our swimming gear, and now we’re gonna run to that pool as fast as our tired feet can carry us.”

– from my journal

Our dinner destination was a swanky Italian joint in Yuma’s historic downtown district called “Da Boys”, a mafia-themed pizza and pasta emporium. The garlic-brushed and cheese-baked breadsticks came with both traditional and meat marinaras for our dipping and dining pleasure; we scarfed through several bowls of each, trying to determine which one was our favorite. By the time the pizzas materialized, we were stuffed… but they looked so damn delectible, we ate them up anyway. We tried to walk off the fat-and-carb overload by strolling around the city center, enjoying the nightlife and the history, but to no avail. That big ‘ol bed was beckoning loudly, and we were so exhausted that we weren’t in any real position to argue.

The game is on. It’s Sunday morning, and Renee and I back at Kennedy Skatepark, gearing up to get down with some early-morning carving. There’s a low-hanging cloud cover that is keeping the sun’s rays at bay, and the temperatures are remarkably mellow. Renee looks a little bit unsure about this whole inclined-wall business, but my enthusiasm is undeniably infectious. Within minutes, she’s following my intrepid lead and warily rolling into the ditch for the first time. She turns up and across the opposite wall, confidently cruises through the flat, and swiftly steers herself back up to the platform as if there’s nothing to it at all. What can I say? She had it in her the whole time. The gal is a natural.

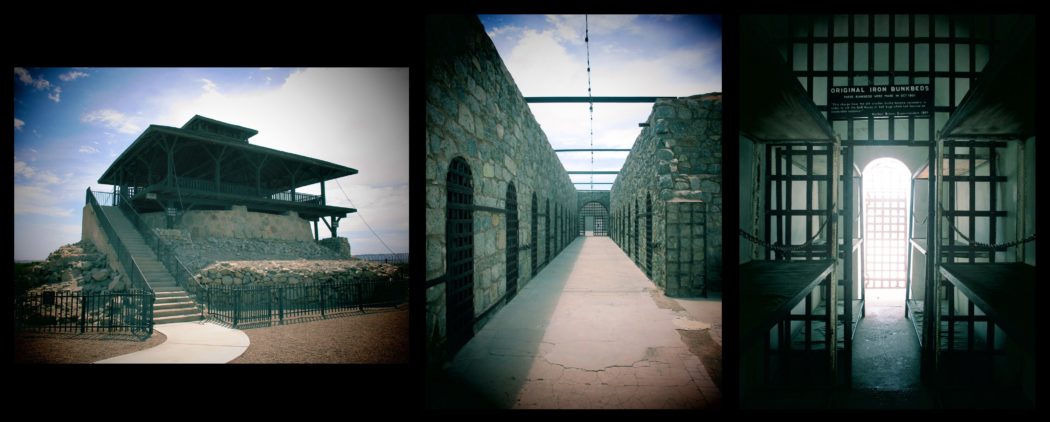

“The Hell Hole” is an apt nickname for the Yuma Territorial Prison. Being an inmate here must have super-sucked. There’s a long list of dubious “crimes” that could have landed your unfortunate ass here… polygamy, armed robbery, murder, or being a rebel-rousing union organizer among them… and very few ways out. Tuberculosis, heat exhaustion, exposure, and insanity claimed a number of lives here; the testimonial graveyard sits high on a bluff overlooking the meandering Colorado River. The steel-matrix reinforced concrete and stone cells held up to six men apiece sleeping on steel beds; a small steel bowl served as the communal toilet, and the daily diet consisted of simple bread and water. Yet this prison was considered the height of “humane” and “sanitary” for its time. I’d hate to see what the inhumane and unsanitary prisons looked like.

Above, left to right: the guard tower, the cell block, and the (scary) interior of a cell. Yuma Territorial Prison, Yuma, Arizona.

As I was busily buying up my usual piles of postcards for friends and family back home, I found one that depicted the gate guards at the Marine Corps Air Station. “Gate Guards”, if you don’t know, are those old airplanes that are mounted up on pedestals outside your local airports and military bases. MCAS Yuma seemed to have quite a quiver of ’em standing outside their gates. I asked the sales guy for directions to where I might find them in person.

“Oh, they’re not there anymore. They’re long gone. Have been for years.”

“Are you sure about that…?” This sounded like pure horseshit to me.

“Sure am, sir!”

“Are you positive…?!” Sorry. It still sounded like horseshit.

“Sure as the day is long!”

“Well, alrighty then”. I put the postcards back in their slat. That would end up being the biggest mistake that I’d make all weekend.

Above: Ocean To Ocean Bridge (left) and Southern Pacific 2521 (right), Yuma, Arizona.

The final mission of the day was to go check out the validity of our postcard salesman’s assertions over at the Marine Corps Air Station Yuma. For some reason, I had my fair share of suspicions that this fine fellow might be completely full of catcrap; once an air base puts up a multi-million dollar “gate guard”, they are generally disinclined to take it down for almost any reason.

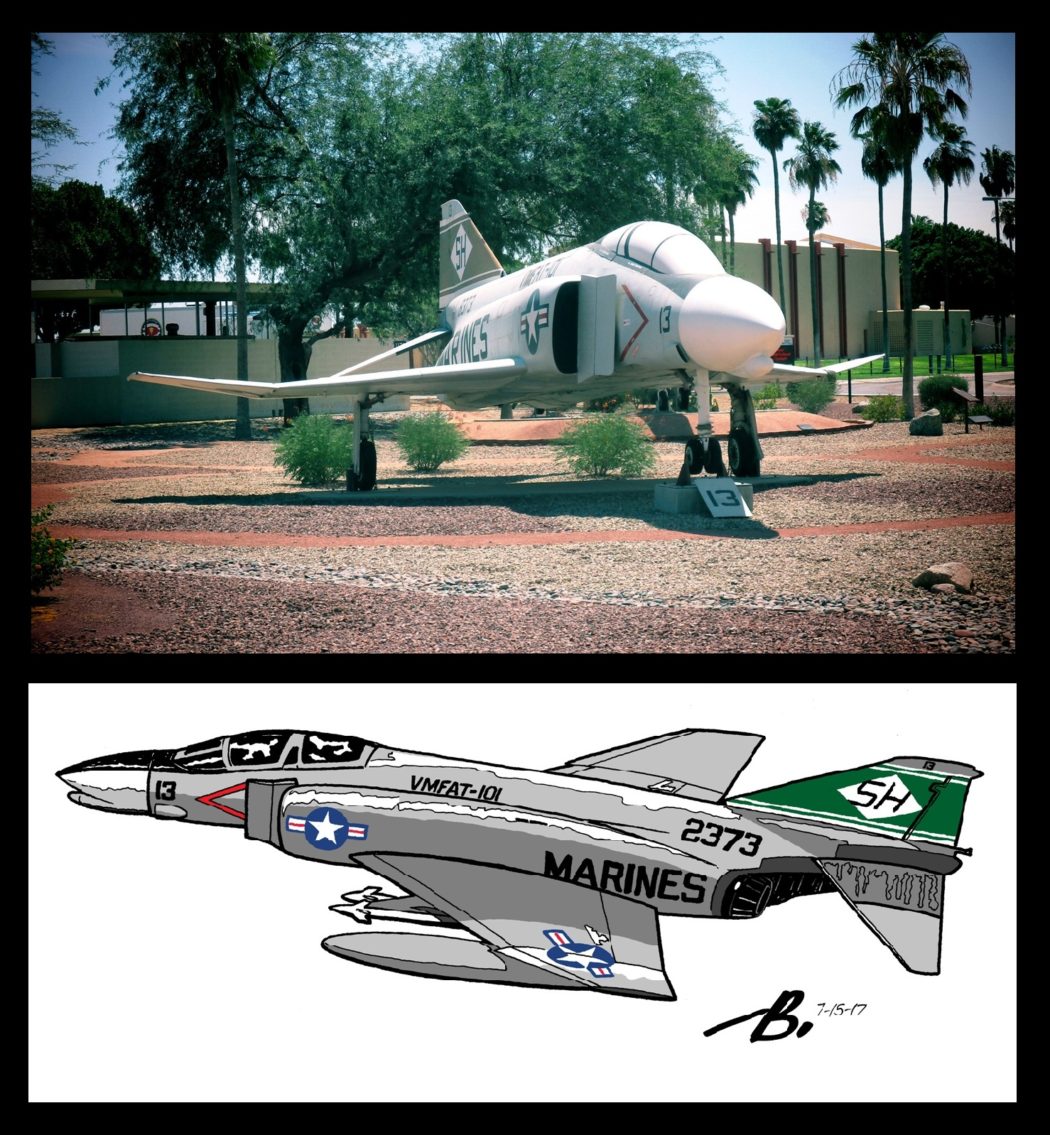

As we drove over to MCAS Yuma, my suspicions proved to be immediately founded. The planes were there, alright, baking away in the desert sun, exactly as I expected to find them; you could see them standing proud at the gates from nearly a mile away, for pete’s sakes. F’n postcard salesmen. If you can’t trust them, then who in the hell can you trust in this world anymore…?

Having found my favorite quarry of the bunch… an F-4B Phantom II… I casually approached the perimeter fence with Renee in tow, quietly stuck the lens of my camera through the chain link fence, and silently started to frame up and focus on my beloved subject for my shot. Just as I was getting ready to click the shutter, I heard excited shouts of “Hey, sir! Sir! Sir…!!“ from far off to my far right, in the general vicinity of the guardhouse. I knew right away that those voices were probably directed at me, and that I was probably in some sort of trouble. That happens a lot in my life, so I’m getting pretty used to it by now. I just wasn’t sure exactly why I was in trouble this time around. But I was definitely about to find out.

Renee and I were immediately detained by the Marine Corps. In the nicest of possible ways, of course. We certainly didn’t feel threatened or anything, just slightly perplexed. We were on a public sidewalk, after all, taking pictures of an obviously public display in a pretty public place. So, what in the good grace of God could be the problem…?

The Marines kindly explained that the angle I had chosen to shoot my beloved Phantom also had the potential to divulge “potentially sensitive national secrets”. Put another way: it was the stuff behind the Phantom (that I hadn’t really noticed) that was causing Renee and I our immediate grief. Ahh. I see. Well, would our kind Marines consider maybe escorting me to a slightly less sensitive spot to take my touristy photos…? Is that a possibility, fellas…?

Their initial answer was a pretty solid “No”. Renee immediately started to protest, but I held her at bay and encouraged her to be patient (and quiet); arguing with heavily armed guards is never the smartest of strategies. And besides, I could feel that my perpetual good fortune was about to kick in.

Just then, somebody important… I’m not sure who he was, exactly, but he certainly seemed like somebody you really wouldn’t want to f’k with… came on over and asked the guards what in Sam Hell was going on. The Marines explained the situation, and Mr. Important quietly advised them (in hushed tones) that it might be in their better interests to escort me about the place. I have no idea why this happened, by the way; I’m certainly nobody “important” at all. But I got my escorts, and I got my way, so I definitely wasn’t gonna be the halfwitted dumbshit that raised any protests at this juncture.

My Marine escorts were remarkably fine chaps. They seemed a little hesitant at first… but once they asked me what my story was, they thawed up quite a bit. That story, by the way, is that I have traveled all over the country taking photos of F-4 Phantoms, and have amassed quite an impressive collection of ’em. So, naturally enough, anytime I travel and come across another one, that becomes my big mission of the day. Simply put: I’m a Phantom Phanatic. Apparently my guards were, too, because once they heard my story, they suddenly became a hell of a lot nicer, and infinitely more cooperative. I got a lot of great snapshots that I was pretty proud of. It was a really grand time, and I’d like to thank them profusely for not throwing me in the brig or the pen.

Above: The “stealth” shot, and the art. F-4B Phantom II, MCAS Yuma, Yuma, Arizona.

The best shot of them all, however, was the very first one that I had silently taken through the fence. Thankfully, nobody had heard the shutter click in all the hubbub; if they had, my camera might well have been confiscated by Uncle Sam Himself. And it was a great photo, definitely the best of the whole bunch.

So, yeah, I was justifiably proud of my well-honed, punk-rock sleuthing skills. Quiet cameras are still the best stealth measures that money can buy.